Many materials used in smartphones, electronic devices, and energy-related technologies are composed of inorganic compounds. While these materials exhibit high stability and functionality, their synthesis has traditionally required high-temperature, energy-intensive processes.

Shinji Noguchi, Specially Appointed Assistant Professor (Ambitious Special Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Advanced Life Science), is rethinking conventional approaches to materials synthesis. By focusing on the “place” where chemical reactions occur during material formation, he explores new possibilities for inorganic materials synthesis.

What kind of research are you working on?

My original field of expertise is inorganic materials chemistry. I have conducted research on novel synthesis methods for inorganic compounds[1]as well as their structural control[2], [3]. Inorganic compounds—materials primarily composed of elements other than carbon—are generally synthesized under high-temperature conditions and require large amounts of energy.

Since my student days, I have been interested in whether inorganic materials could be synthesized under milder conditions, and I have continued my research with this question in mind. Currently, by applying my background in inorganic materials chemistry, I focus on the mechanisms by which living organisms synthesize materials within their bodies, and I aim to artificially design such environments to enable new approaches to materials synthesis.

How are living organisms related to materials synthesis?

Bones and teeth, which constitute our bodies, are also inorganic compounds. Living organisms precisely synthesize and control these materials under extremely mild conditions—ambient temperature and pressure.

These biological material synthesis processes achieve highly functional materials with remarkably low energy consumption, making them highly rational from a materials science perspective. I believe that it is crucial to focus on the environment itself that enables living organisms to synthesize inorganic materials.

What methods do you use in your research?

At the Laboratory of Convergence Soft Matter, where I am currently affiliated, research is centered on polymeric materials. Within this framework, I utilize polymeric materials known as hydrogels for inorganic compound synthesis. Hydrogels consist of polymer networks that retain large amounts of water, giving them soft, tissue-like properties similar to those of biological systems.

Rather than treating hydrogels merely as biomimetic environments, I actively design them as reaction fields—spaces in which chemical reactions leading to inorganic compound synthesis occur.

By controlling the network structure and mechanical properties of hydrogels, I investigate how the morphology and functionality of inorganic compounds synthesized within them can be regulated.

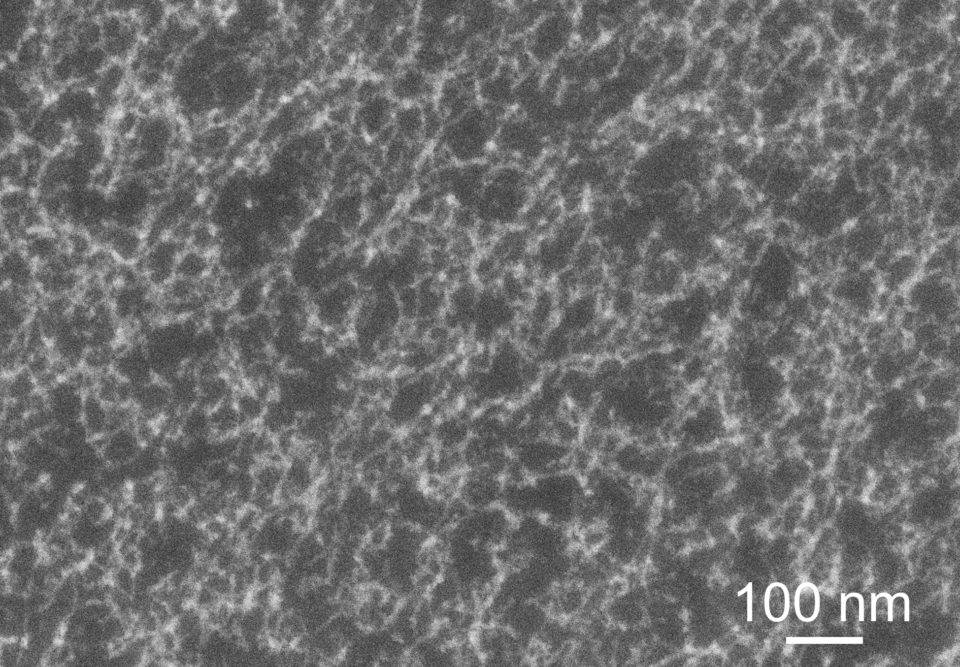

To date, we have successfully synthesized titanium dioxide—used in applications such as photocatalysts—in a nanoscale, network-like morphology that follows the polymer mesh structure by tailoring the hydrogel architecture used as the reaction field[4]. (This work was conducted in collaboration with Associate Professor Takayuki Nonoyama, the principal investigator of the laboratory.)

This approach, which starts from polymer design to control the morphology of inorganic compounds, has the potential to create inorganic materials with structures and functions that could not be achieved through conventional methods.

(the scale bar at the lower right corresponds to one hundred-thousandth of a centimeter).

Why did you decide to become a researcher?

An encounter with a mentor once profoundly influenced my career path. I was told:

“The professions that can save the greatest number of people are politicians and scientists.”

This statement became a major motivation for me to pursue a career in research. Many of the challenges humanity faces—such as conflict, famine, and environmental problems—require fundamental solutions driven by science and technology. Equally important is establishing systems that allow these solutions to be widely disseminated and shared by society.

Research offers the opportunity to generate new knowledge and technologies and return them to society. I found this potential deeply compelling, which led me to choose the path of a researcher.

Although challenges such as energy issues and global warming are far from easy to solve, my participation in the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings(※) profoundly shaped my outlook. Through discussions with Nobel laureates and peers selected from around the world, I strongly felt that, together, we can contribute to solving global challenges through science and technology.

In the future, I hope to leverage my experience as a scientist to serve as a leader who passes scientific knowledge on to the next generation and connects collaborations across countries and disciplines.

(※) An international conference held in Lindau, Germany, where Nobel laureates and selected young researchers gather and interact.

Second from the right: Shinji Noguchi; third from the right: Dr. Steven Chu (Nobel Prize in Physics, 1997).

How do you plan to advance your research in the future?

Inspired by the way bones strengthen in response to mechanical stress, I am currently working on research that applies mechanical stimuli to polymeric materials to synthesize and grow inorganic compounds within them.

The challenges are substantial, but I believe that by designing polymeric materials from perspectives no one has yet considered—and by controlling the inorganic synthesis reactions occurring within them through approaches unique to my expertise—these goals can be achieved.

If successful, this research could lead to applications in bone therapy. Furthermore, as humanity expands into space, it may offer new solutions to bone weakening caused by microgravity environments, such as those experienced in outer space.

Watch this.